BnL is a company that sells everything and anything

…but it’s not just any company, it’s also the leader of world government.

(or at least it is in the Wall-e (Pixar) universe)

This is quite an interesting scenario, and something that actually seems relatively familiar to us in our world of consumerism and multinational supermarket chains, in which everything one needs can be purchased/ordered/delivered/ to anywhere on the planet

The reality is, that we have many ‘BnL’s in the marketplace, offering us everything we could ever need, under many different names, brands, and companies.

One of the obvious examples of this are the big players such as Unilever, Mars, P&G, Pepsico, and Coco Cola. These companies own vast swathes of the products we all know and repeatedly buy, and we often don’t consider the ‘bigger picture’ of who owns the companies that own the products.

Often these mega companies don’t significantly advertise their involvement in the brands they own, for fear of backlashes for owning brands with conflicting ideologies (such as the Lynx/Axe – Dove relationship). Or perhaps they’re worried people won’t like the idea of superbrands owning everything…

However, when they do acknowledge themselves as owners of their products, it’s known as umbrella branding.

Umbrella branding allows companies to extend product and brand lines, whilst still being able to use their name in order to allow consumers to make inferences about the new products based on their views of the larger ‘umbrella’ brand (Hakenes & Peitz, 2008). For companies, this reduces the overal costs of bringing out new products.

Take a company such as Virgin, if you had gained experience of the Virgin voyager train service, would that influence your perception of their Virgin atlantic service if you had never used it?

Hakenes and Peitz, (2008) further investigated how product quality is influenced by umbrella branding. They found that umbrella branding did demonstrate an effect on how novel products were perceived when put under the umbrella of another brand. It was even found that products that were viewed positively under the umbrella, could be viewed negatively without it.

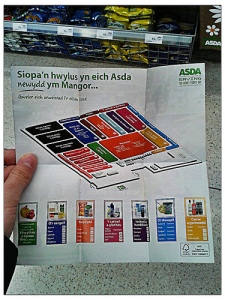

Arguably, even supermarkets are setting themselves up as mega brands, offering everything one needs as well as their standard groceries. If I pop to Tesco online, not only can I pick up a pint of milk, but also: insure my cat, purchase a DSLR camera, set up a mobile phone contract, buy a t-shirt, and even take out a mortgage for my house. Laforet (2007) further investigated how customers perceived supermarket brand extensions in relation to finance. It was found that within three different retailers, the financial services were seen as trusted, in relation to the overal brand of the retailer. This could further demonstrate that if the overal brand of a company can appear trustworthy (this includes the risk of purchasing for the consumer), then they can extend their brand to nearly any other product or service.

This suggests that the mega brands, could only grow bigger, either through umbrella branding, or under the guise of other companies the mega brands own.

So when the world has run out of resources, the sky has been scarred from pollution, and humanity has finished it’s final stand, will it be a Unilever spacecraft that we board to take us away and save us? A P&G teleportation device to deliver us to safety? Or perhaps we will pop over to the planet Mars brought to you by Mars©. All of them still brimming with all the consumerism we could ever need to entertain and nourish us.

I think I’ve just managed to frighten myself.